Saul Kent: Some Recollections and Reflections

Recently Saul Kent has become a cryonics patient at Alcor. It was after a long and productive career of activism and accomplishment in areas related to extending human lifespan and healthspan. Prominently, it included cryonics itself, where Saul was a major player almost from the very beginning of the movement. Later Saul and his business partner Bill Faloon organized the Life Extension Foundation (now Biomedical Research and Longevity Society) whose revenues from the sale of dietary supplements were used to fund research in cryobiology and organ preservation. In all they stand above all others in their financial backing of research relating to cryonics and life extension. We owe them a great debt.

I was not part of Saul’s (or Bill’s) enterprises either as an employee or other associate, thus much of what Saul accomplished, if you are going by personal reminiscence, is better related by others. But I do have here some recollections and reflections from a long involvement of my own in cryonics, where Saul was not that far away, and sometimes did interact at a personal level.

By way of background: I first heard about cryonics (not under that name) in the fall of 1965 as an 18-year-old college freshman (University of Chicago). Why not freeze (or cryopreserve) the newly deceased, before any serious deterioration can set in, in hopes of revival at a future time when technology would be more advanced than it is now? I had actually thought of the idea before anyone else mentioned it to me, but concluded there must be some reason I didn’t know about that would preclude it working. Granted, it was well-known that frozen human organs did not resume function on thawing, no matter what else you did. But on the other hand, what if you just kept them frozen for a future time when technology would be more advanced than today? You could hope that then, there might be procedures available that could bring about a desired revival. You could do this with the brain, and perhaps a whole human body, or build back parts of the body that were missing, as long as you had the brain with its personality-defining features reasonably intact. And I soon decided, mainly from talking to a college roommate who, like me, was also a science fiction fan, that no, there was no known reason the idea couldn’t work. The future ought to have many wonders, and I determined to undergo this cryopreservation myself as a possible way to beat death, though also thinking it no matter of urgency right then.

Anyway, to return to the main focus of this article, at this time there was a small group of enthusiasts who also had similar ideas, and (unlike me, the college kid barely out of high school) were trying to implement them and publicize the idea to the general public. Among them was Saul Kent who would have turned 26 in 1965 and was a founding member of the Cryonics Society of New York, formed that summer. The previous year he had his first exposure to the cryonics idea, reading Robert Ettinger’s just published book on the subject. It was an epiphany: “When I read The Prospect of Immortality in June of 1964, I was exhilarated to a degree I had never before experienced. Instantly I knew – beyond a shadow of a doubt – that the most profound and powerful idea in history had been unleashed and that I would devote my life to it.”1

Fast forward about a decade, to the mid-1970s. Much drama had played itself out in the nascent cryonics movement, though I was mostly oblivious of this. My first significant exposure to the cryonics community came in 1974 from reading Ettinger’s second book, Man into Superman (1972), a speculative projection of what sort of future one might expect (a very good one, in fact) if one could be revived in a time when now-terminal ailments could be cured. (I didn’t encounter Prospect until several years later. As good as it was, I have always thought the other volume even better. As a side benefit it also mentioned cryonics, which hadn’t been coined when the first volume was published, so now I was familiar with the term.) My active involvement started with answering an ad that appeared in the August 1976 Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. (I found the issue in a drugstore, probably the time was around mid-July, in Boulder, Colorado, where I lived almost continuously for about 15 years, starting in 1971.)

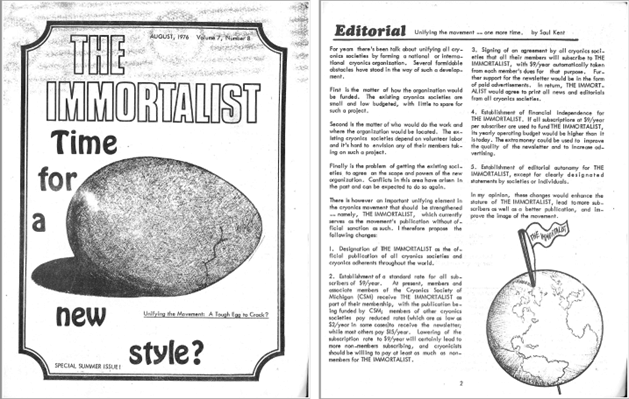

The ad offered, for $3.75, a five-month trial subscription to The Immortalist, “newsletter of Cryonics Society of Michigan,” which, it said, “publishes news of all medical and social advances relating to cryonics and immortality.” I sent my money. The first issue I received, also dated August 1976, showed an egg on the front cover with a cracked shell, with a caption suggesting that unifying the movement might be a “tough egg to crack.” Inside was an editorial by Saul Kent elaborating on this theme and offering some suggestions.

Unifying the movement? Up to that point, and despite reading Superman, which actually had few details about the ongoing practice of cryonics, I had no impression of any “movement” needing to be “unified,” any more than I would if I wanted some unusual mortuary practice. You just went to the right people, expressed your wishes, arranged for the funds that would be needed, it was all straightforward, right? Anyway, another thing I didn’t realize was that, while a few years before, there had been several newsletters from different groups all devoted to the practice, by now these had dwindled so that what I was reading was almost the only cryonics newsletter being published. (Actually, the fledgling Alcor organization of the time had also started a small, in-house publication, Alcor News, but this was not very widely circulated. There may have been other, limited publications too but nothing else as far as I know for the general readership.)

At least this one publication was going strong, which explains the emphasis Saul places on having it as mouth organ for a projected “national or international cryonics organization.” As it turned out, the “egg” would still prove “too tough to crack.” There would be no unifying organization, different groups would start publishing their own newsletters again, alongside The Immortalist (which continues today as Long Life). The inclusion of “one more time” in the editorial’s title hints at past efforts to accomplish the same thing, which had ended in failure. It would be nice if all cryonics organizations could unite and work together as a team, but this goal has proved elusive. More realistic is that organizations can be reasonably supportive of each other’s efforts and assist each other in limited ways, while essentially pursuing independent paths. This I think has largely occurred over the years, with some exceptions, and Saul was generally favorable and encouraging, though also pursuing his own special interests.

The Immortalist, August 1976; cover, and Saul Kent’s editorial.

Now fast forward seven more years. Still living in Boulder, I had been a signed up cryonicist for most of this time and was working on my dissertation for a Ph.D. in computer science. I had kept contact with the cryonics community and received newsletters, but had not been personally active otherwise, being busy with graduate school. At that point, I had never seen another cryonicist face to face. Saul Kent meanwhile had continued his activism, both in cryonics, where he decided to relocate to Florida and help organize a group there, and also in the field of nutritional and dietary supplements to improve health and longevity.

In July that year there was a nutrition conference in Boulder that Saul attended and on the 23rd he and Dayna Dye, who then was an administrative assistant for a health organization in the area,2 paid me a visit. For an hour and a half we talked about cryonics and Saul inspected my paperwork, then with the Cryonics Institute. Goodbyes were said and the two departed.

Saul Kent and Dayna Dye on their visit to the author in July 1983.

Another four years went by. I had gotten my Ph.D. and was now working at Alcor’s facility in Riverside, California, on tasks like checking dewars, answering phones, filing documents, and keeping the place neat and tidy, things that didn’t exactly require a doctorate in computer science. Well, this was only temporary, I thought, I’d soon have some sort of programming job, maybe doing research in artificial intelligence, which was a special, strong interest.

What happened next was one of those pivotal events that make for interesting reading later, perhaps, but are not much fun to live through. It was December 1987. Dora Kent, Saul’s mother, was in poor health and had pneumonia. She was brought to the Alcor facility in Riverside and arrested there. She was cryopreserved (as a neuro). No physician was present but that didn’t seem a problem because cardiac arrests happened all the time in nursing homes and the physician later paid a visit and signed off on the death certificate. In this case though, we were not a nursing home but had a very unusual practice of cryopreservation, and the coroner decided to investigate. As part of the investigation, he wanted to autopsy the entire body, including the part we’d frozen (head or cephalon, containing the all-important brain) that was now resting in liquid nitrogen. No amount of pleading could change his mind, even though the rest of the remains were given up and processed and at first the cause of death was ruled pneumonia, from natural causes. Soon however the finding was changed to homicide, based on the suspicion that Ms. Kent had still been alive when our procedure was started.

So Saul went to court. The upshot was a finding of “no evidence of foul play” plus a restraining order that forbade the coroner from disturbing the cephalic remains of Dora Kent, and also any other cryopreserved remains in Alcor’s custody (these, covering several other patients, had been wanted at one point for “identification”). Before this happened, though, there were “interesting times” at the facility. At one point, six of us were rounded up, placed in handcuffs, and carted off to the police station. (For the record the six were, last names in alphabetical order, Mike Darwin, Hugh Hixon, Arthur McCombs, Carlos Mondragon, Mike Perry, David Pizer.) An attorney of ours who normally handled more mundane matters like building permits and zoning issues (his name was Trip Hord) visited us in our detention. He noted to the authorities that we were not being held for valid reasons, and we were released after having sat maybe a couple of hours with our hands bound behind our backs. (Eventually a lawsuit was filed over this, and an out-of-court settlement of $90,000 was agreed to, divided between the six of us and our attorney.)3

Through this and other tribulations connected with Dora Kent, it was reassuring to keep in mind that Saul was tenaciously pursuing matters, with funding coming from his life extension business. Attorneys like ours (not just specializing in building permits) were not cheap, and a coroner’s decision to autopsy was hardly ever overruled, as had happened with us. Moreover, although there was compensation to the six of us from the other side, in general there was no such remuneration and most of the financial burden for defending Dora Kent had to be covered by our side.

At one point the coroner seemingly had a case against us. Examination of the body fluids showed cell metabolites intermingled with our perfusate. This “had to mean” Dora Kent was still alive when we started our procedure. But we countered that metabolic support is routinely given postmortem in our cases, including oxygenation of the tissues as a way to minimize cell deterioration during the cryoprotection phase, before cooling to low temperature. Cells do not instantly die when cardiac arrest occurs and oxygen-bearing blood stops flowing. If supplied with oxygen from some other source, normally a very unusual circumstance, they can still produce metabolites. In the end no charges were filed against Alcor.

Soon, however, another crisis loomed. In March 1988 Alcor’s did its first whole-body preservation; of a gentleman from Florida named Robert Binkowski. The California Health Department objected, said we could not continue because we were not licensed to do what we were doing. When we inquired as to how we could obtain the necessary license, we were told that there was no way to do that. The state’s licensing system had no provision for this newfangled “cryonics,” we would just have to cease and desist, at least for whole bodies. (For neuros we could specify “cremation” for the main part of the remains, with the portion preserved as a “tissue sample.”) Again, there was a big court battle, this one costing over $100,000 in legal fees and countless hours of work by Alcor staff. Saul Kent also spent tremendous effort helping to direct and promote the suit. Finally, the effort paid off and we won the right to fully practice cryonics in California.4,5

The two crises had the consequences that someone was needed at the facility to handle the ringing phones and otherwise keep the facility operational. In the worst part of the earlier crisis, following the detention of the six of us, my very inexperience as a newcomer meant that I was more expendable than the others should there be another arrest. I was often alone at the facility, clearly someone whose presence was needed. My projected departure for the inviting land of computer geekhood was postponed. Meanwhile there was time for reflection. Cryonics in my mind proved that mainstream science could in fact address the problem of what to do if you are dying today, not just in some future time when more advanced techniques had been perfected. But it wasn’t doing that. In the end I would stay on with Alcor as a cryonics technician, writer, computer programmer, and mathematical researcher, and I would say, not particularly regret it either. Would I have done better with full-time work in AI? Any choice you make leaves alternatives that might have been better – or not. But we do live still, in spite of any progress we’ve made, in a world of death, which is always there in the background, whatever your occupation. How do you want to cope with that?

Two special patients. The cryopreservations of Dora Kent and Robert Binkowski provoked lengthy and costly legal confrontations which, however, ultimately strengthened Alcor and cryonics. Financial and other support of Saul Kent and Bill Faloon in these crises was critical.

Saul Kent and Bill Faloon meanwhile were occupied with other legal battles, connected with their dietary supplement business, but fortunately this did not usurp all their resources. For many years they supported work in cryobiology and organ preservation, really mainstream efforts which just happen to have relevance to cryonics, work that continues today under Bill’s still-dedicated sponsorship.

The history of cryonics and Alcor after the two legal crises was sometimes rocky, and Saul made enemies, particularly with a split in Alcor in which some of the members formed a new, rival organization, CryoCare (not to be confused with the much earlier CryoCare Equipment Corporation which manufactured the early horizontal cryogenic capsules for whole bodies in the 1960s.) But after a few years CryoCare ceased its operations, its patients were transferred to other organizations, some to Alcor, and most of its membership returned to Alcor, Saul among them. He had been on the board of directors before the split, and he later returned and served for several more years.

Saul for many years was enthusiastic and optimistic about the prospects of cryonics and human life extension. Finally, however, I’m told he became discouraged and doubted it would all come true as he and others had proclaimed. But he stuck it out anyhow and now we have the opportunity to vindicate the earlier positive outlook.

Rest in peace for now Saul; we must get you back!

References

1. Saul Kent, “The First Cryonicist,” Cryonics #32 (Mar. 1983) 9.

2. https://www.linkedin.com/in/dayna-dye-5380a95/, accessed 12 Jun. 2023.

3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dora_Kent, accessed 14 Jun. 2023.

4. R. Michael Perry, “An Institutional History of Alcor,” Cryonics 43(1) (1Q 2022) 36.

5. https://www.cryonicsarchive.org/library/big-california-legal-victory-affirming-the-right-to-be-cryopreserved/, accessed 14 Jun. 2023